It’s personal, isn’t it? What personalization means for internet research methods

By: Elinor Carmi, New Political Communication Unit, Politics & International Relations Department, Royal Holloway, University of London.

“It wasn’t uncommon to have 35 to 45 thousands of these types of ads everyday“ said Theresa Hong, the Digital Content Director of Donald Trump’s Project Alamo, to Jamie Bartlett about the way the digital campaign team personalized advertisements on Facebook. Project Alamo was conducted in collaboration with Cambridge Analytica in the USA 2016 election, to profile people and tailor thousands of messages according to particular audiences with perceived characteristics. Hong was speaking to Bartlett as part of his two piece documentary for BBC2 – the Secrets of Silicon Valley – which was aired in august 2017. The documentary gave a glimpse to some of the digital advertising industry’s practices that during the past decade have become a standard in this industry. The holy grail is personalization.

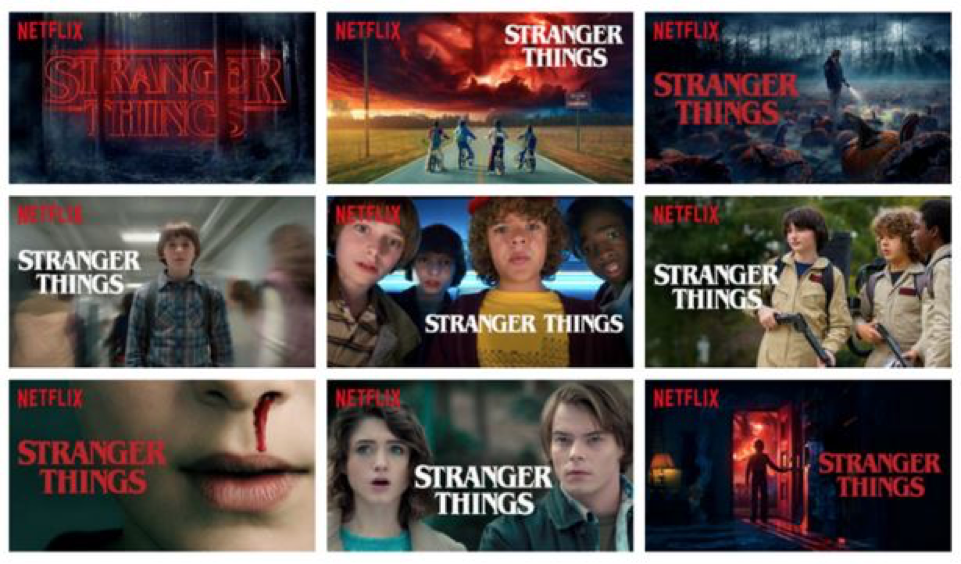

But such personalizing of content does not only happen when it comes to political advertisements. On December 2017, Netflix revealed that it is personalizing the artwork and imagery shown on its films and television series thumbnails according to its subscribers’ profiles. As the technology blog of the company indicated, Netflix differs from traditional media as it doesn’t “have one product but over a 100 million different products with one for each of our members with personalized recommendations and personalized visuals”. The other more commonly known system of personalization is their recommendation system. The company operates “a great built-in way to only suggest content we think you’ll love based on your viewing history. The more you use Netflix, the more relevant your suggested content will be”. In this way, Netflix conducts two types of personalization – content (Stranger Things series will show a thumbnail of the female characters for me) and sorting (Stranger things will be the most recommended show for me, indicating 99% match following my love for science fiction and 1980s films).

Personalization is an ideology that Silicon Valley has promoted as the prefered way to experience the web, the default design of our life. Many of the services people use are algorithmically designed according to this approach, because it is directly tied to the business model they offer – free services in exchange for more relevant ads based on the profiles created on them. From search engine results, to trends on social media and onto recommended apps, music, videos, films or books – We get tailored experiences. Consequently, when we engage with information on the internet, we receive personalized material that matches us, and others who have similar preferences, habits and characteristics.

Stranger Things different thumbnail art for personalization. Source: https://medium.com/netflix-techblog/artwork-personalization-c589f074ad76.

Stranger Things different thumbnail art for personalization. Source: https://medium.com/netflix-techblog/artwork-personalization-c589f074ad76.

But although scholars use the term personalization quite often, it does not have a distinct definition. Zuiderveen Borgesius et al (2016) argue that there are two types of personalization – self-selected, which is “situations in which people choose to encounter like-minded opinions exclusively” and pre-selected which is “driven by websites, advertisers, or other actors, often without the user’s deliberate choice, input, knowledge or consent”. But as personalization is getting tailored deeper into our everyday life, the notion of selection gets complicated, and it is difficult to understand the agency that each entity has in this process. Is this only about a selection? What kind of choices do people have in these situations? Can algorithms nudge us to make a specific choice? How do we account for people’s choices who are not visible or immediate?

The question is not only whether people or platforms sort, select, suggest and rank information according to specific decisions. It is not only about the event of selection, but rather the events that came before and that – it is a process. This is especially the case as algorithms do not operate in a single procedure but rather collect, combine, process, rank and sort from different people, databases, times and places. But people also do not operate in a single isolated event – usually several tabs/apps/devices are operating simultaneously where we can slide between watching the new episode of the Handmaid’s Tale, while writing spoilers about it on the family Whatsapp and listening to the new Janelle Monáe album. In between we are reading the Irish abortion referendum being repealed on the Guardian and posting it on Facebook while having to write another happy birthday to someone you’ve met twice. We engage with information in various ways that go beyond selection on many platforms, apps and everyday life situations. So what is actually at stake here?

As our experiences in various spheres shape how information is sorted by algorithms or us – it is important to examine individuals’ life in a social context. In short – personalization is not about the individual experience but people’s social experiences and their complex intersections with multiple contexts. So depending on what researchers aim to examine, they need to consider more diverse types of networks as they are the entry and end point(s). Stuart Hall’s seminal work can assist here, as personalization process relies on people’s network to encode content and ordering but they also affect the way people decode these things. How can researcher approach these complex assemblages.

Tailoring research to personalization

How does the personalization approach affect the way internet researchers conduct research? The immediate topics in relation to this seem to be around ‘filter bubbles’ and eco-chambers, which some scholars refute and argue that we need to minimize the influence we give to these algorithmic sorting. But while there has been a lot of attention on personalization in terms of news and politics, this also has an influence on research areas such as subjectivities, interpretations, interactions with other people and objects, world views, preferences and even jobs. This is then a complex process that happens simultaneously, where both content and sorting are personalized and tailored to people which focus on individual but also their networks.

Previously in academic research on algorithms the focus was on the type of sorting a platform shows people. The most famous example can be seen in Taina Bucher’s excellent article from 2012 “Want to be on the top? Algorithmic power and the threat of invisibility on Facebook”. In that article, Bucher conducted an auto-ethnography where she examines her own Facebook newsfeed and compares the Top News (later to become Top Stories) and Most Recent by capturing screenshots of the items that are presented to her over a period of two months. Bucher examined the sorting mechanisms by focusing on an individual experience of personalization. More recently, Safiya Noble shows in her book Algorithms of Oppression how people of color experience personalization of search engines differently and what are the dangers of baking racism and discrimination into algorithms.

Personalization then, is a complex interplay influenced by people’s individual online behaviour and their social networks, tuning in into micro and macro behaviours. If we take anything from the Cambridge Analytica’s scandal, it is that individuals’ friends and networks matter – personalization is dependent on social networks. As Netflix argues, the company recommends things according to a ‘global’ approach for communities: “Netflix’s global recommendation system finds the most relevant global communities based on a member’s personal tastes and preferences, and uses those insights to serve up better titles for each member, regardless of where he or she may live”. Similarly, Spotify’s Discover Weekly feature offers an experience “based on your listening history and that of other Spotify fans with similar tastes, it gets even better the more you use Spotify”. Contrary to the feminist approach of situated knowledge, what we see here are ‘global communities’ that are algorithmically created. This is done without taking considerations to what communities people actually consider themselves to be part of. Some of the risks of that, as Anna Lauren Hoffman argues, is enacting data violence according to choices which engineer such ‘global communities’ and platforms.

Directions for future research

So what kind of things should researchers take into consideration when examining personalization? The way that audiences are being produced by media companies (in its broadest sense) is changing. The segmentation of audiences is fast changing into more nuanced categories which are more related to interests, behavioural traits and experience, rather than more traditional sociological ones (age, gender, location). As Hong said in the Secrets of Silicon Valley documentary, Cambridge Analytica targeted people according to what they call ‘universe’, meaning they were looking at: when was the last time people voted, who did they vote for, what type of car do they drive, and importantly – what kinds of things do they look at when on the internet. Furthermore, such companies also look at things like emotional and personality traits such as whether people are introverts, fearful or positive. As always, there is no one magical method to understand what is going on. But here are several directions to consider:

- How the social is reconfigured – It is easy to focus on individuals because personalization is framed as an isolated experience. But as personalization feeds from our networks we might want to examine how do people engage with other people and how do they manage this interplay of individual and social experience in these spaces? Importantly, how does personalization mix with everyday life experiences. For example, I receive particular recommendations from Netflix according to my behaviour and the global community associated with my patterns. But I also get recommendations from my brother, random people I follow on Twitter, people I meet in pubs and house parties and so on. In a way, we can take Alice Marwick and danah boyd’s context collapse concept and adjust it beyond how we present ourselves in different digitally mediated spaces. We can start examining how people manage and engage with the information that is presented, recommended and ranked from different spheres whether digitally mediated or not.

- More comparative and collaborative work – If people are shown different sorting and content it is important to examine what kinds of variations are presented to people. But exactly to counter technology companies’ assumptions about ‘global’ communities and their preferences, researchers can start to engage with communities to better understand how they experience personalization. In a recent article on embracing feminist situated knowledge approach to researching big data, Mary Elizabeth Luka and Mélanie Millette propose an ethical practice of care. Particularly productive to personalization, they propose engaging with communities and involving them in the whole research process. This can mean participating with communities in different activities and situations and what kinds of tensions and negotiations they experience when it comes to what is relevant to them versus what media companies think is relevant to them. It means collaborating with them on how they interpret, negate, feel, and ignore information navigating and sliding between multiple and complex spheres. Such suggestions can be fruitful to understand how different communities have complex and sometimes conflicting and intersecting experiences of personalization.

- Time and duration – This point follows from the previous one. There is a tendency to focus on single incidents/events of personalization – one search, one recommendation, one news article, and one advertisement. But examining what personalization does, or how it feels and experienced would also mean to follow these procedures for a longer period of time. This is especially relevant as behaviours are collected throughout time and focus on different times as key indicators for personalization. Taking Netflix again as an example here, the service argues that other important things they calculate to provide personalization is “the time of day you watch” and “how long you watch”. Similarly, explaining how their algorithm works to journalists Instagram argues that several time related signals determine what you see on the ‘feed’ such as: recency (how long ago a post was shared), frequency (how often do you open the app) and usage (how long do you spend on the app). Time is important but not neutral. It would be interesting to examine how personalization changes over time, how it constructs feelings of time and how it tailors specific things in particular times. But behaviours are also measured throughout space which leads me to the next point – context.

- Context and design – A recent piece of research on the way Chinese Americans engage with information flow on WeChat shows that the platform’s design encourage a different kind of information flow. It argues that on WeChat people engage with information in closed groups of friends and acquaintances. Contrary to other social media platform are much less influenced by hashtags and trends. What the research suggests is that WeChat prescribes a social curation approach through its design, which also includes weak ties. This is interesting as it suggests that the personalization is not the default of all platforms, and that different types of personalization can work simultaneously. It would be interesting to examine how each platform applies ordering rationales but also how people experience these multiple platforms when they use them together.

- Beyond political campaigns – Although there has been an extensive attention to the way personalization affects politics (from political campaigns, to micro-targeting and news selection), even with great project such as the Political Ad Collector (PAC) from Propublica – it is important to look at politics in a broader sense. If anything, political preferences, opinions and behaviours are just one aspect among many others, that personalization influences and is influenced by. These tailored sorting and content influence aspects which form people’s opinions, subjectivity, identity, as well as their behaviour and options of living. Politics consists of people’s views and practices in all the other spheres in their lives, and so they should not be seen as separate dimensions.

All these possible directions depend on what researchers aim to examine. Personalization is a opportunity to collaborate between different fields, enriching each others’ perspective on this phenomenon. Within media studies, this includes media selection and gate-keepers, algorithmic sorting, audience interpretation and people’s agency. In anthropology it means getting closer to communities and understanding together with them what are their engagements with such mechanisms in different contexts. Psychologists can contribute on what are the emotional, social and personality biases and patterns that can be influenced by personalization. Geographers can help us understand how we experience spaces and architectures differently because of personalization. The list goes on. Personalization is an ideology that Silicon Valley tries to sell us, but at the same time it is important not to assign too much power to its influence. People still interact outside platforms, they get information from everyday life experiences and engagements and these are not always influenced (exclusively) by algorithms. The imagined power of such personalization is just as important, the more we can imagine other ways of engagement the more we open ways to experience our social networks the way it suits us.