4 Inches of Embarrassment: Humour, sex and risk on mobile devices

Kylie Jarrett

National University of Ireland, Department of Media Studies, Maynooth, Ireland.

Email. kylie.jarrett@um.ie

Twitter. @kylzjarrett

Ben Light*

University of Salford, School of Health and Society, Salford, United Kingdom.

Email. b.light@salford.ac.uk

Twitter. @doggyb

Susanna Paasonen

University of Turku, Department of Media Studies, Turku, Finland.

Email. suspaa@utu.fi

Twitter. @susannapaasonen

Early in the 2000s, a link to a website ending in “nimp.org” was circulated via email. The link opened up to a blinking image alternating between a rainbow flag and gay pornography, accompanied by a three-second clip of a male voice amped up high in volume, shouting, “Hey everybody I’m looking at gay porno!” (For a partial, SFW YouTube excerpt, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BN5k-8njOMM.) In addition to the potential social awkwardness that watching this media product at work might have caused, nimp.org routinely froze and crashed the user’s computer by opening up new pop-up windows with the same content much faster than these could be closed. The computer’s sound card could also keep on playing the file even when all windows had been successfully closed. Allegedly connected to the internet trolling organization “Gay Nigger Association of America”, the site’s routine became known as a “nimp”. The nimp relied on the embarrassment caused by loudly calling attention to pornography – and specifically that of the male homosexual kind –being consumed in spaces of work. In work environments of the early 2000s, these links would be opened on desktop computers and laptops in workspaces that readily shared the sight and sound of nimping with colleagues to achieve maximum embarrassment. Nimps are a good example of content we would describe today as NSFW, not safe for work.

The idea of something being NSFW is rooted in a sense that certain engaging online content is associated with potential loss and risk in an employment context. This has also bled into our personal lives as the idea of something being not safe for life (NSFL). Oftentimes, NSFW content is shared and experienced as humorous, partly because of its status as being out of place. There is thus both the potential of pain and pleasure for both the receiver and recipient: NSFW is a tag and label for content that both averts and engages. As nimping demonstrates, NSFW content has been circulated online for decades. In this short piece, though, we want to explore how the move from desktop computing to mobile devices, and from web cultures of the early 2000s to social media, has re-articulated elements of these practices.

Social media, app culture and the ubiquity of mobile devices have increased the number and types of people engaging with online content in both personal and work capacities. Where once only white-collar professionals enrolled mobile phones and laptops to enable mobility in their work, those in other occupations, such as cleaners, porn stars, tradespeople, sex workers and taxi drivers are now regularly engaging with these same technologies.

With advances in the capability of mobile devices for capture and distribution of multimodal content has also come the possibility of sharing a diverse range of media. These developments have, for instance, facilitated selfie cultures, sexting practices and the more pervasive creation and sharing of vernacular photography and video. Alongside this has been growth in the sharing of humorous and NSWF content. Where once a dancing spiderman gif may have been shared with friends or co-workers via email, exchanges of humorous content have shifted to social media and personal mobile devices.

The intimacy and individualization of mobile devices could be argued to offer more privacy than a desktop computer. One might then think that the potential for causing social embarrassment through acts such as nimping no longer exists. However, while mobile devices vary in size due to social, cultural, economic and technical conditions, there has been a shift to them incorporating larger screens. Screens of around 4 inches that can be readily overlooked by others are now considered small.

This infrastructure enables new ways of consciously or accidentally causing surprise and embarrassment that, despite these new sociotechnical conditions, very much resemble the historical practice of nimping. Here we will give two. These examples reflect actual experiences of these activities and follow patterns in real exchanges gathered as part of this research, although Jarrett and Light have here re-created the images due to ethical concerns.

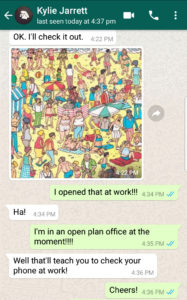

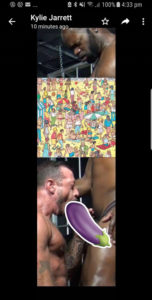

The first example is the sharing of an image that appears to be innocent and safe for work, but which, at closer viewing, decidedly is not. Figure 1 shows what appears to be a detailed cartoon scene of a sunny beach. The image has been sent with no explanation from one user to another and as the image is small, it invites the recipient to touch it in order to see more. Upon expansion, the full image in Figure 2 is revealed, depicting a fellatio dungeon scene from homosexual pornography. As with the nimp, the expected embarrassment of being seen looking at porn of this genre is central to its distribution. On the larger mobile screen, it becomes a possibility that this joke is also publicly amplified as shown in Figure 1 where the recipient laments opening it in an open plan office.

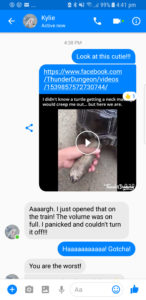

Of course, this response is not restricted to a work context – the sharing of such content remains risky in many public spaces. For example, in Figure 3, video and sound is mobilized as part of the prank in a manner similar to nimping. Opening the seemingly innocent video of a turtle receiving a neck massage plays a file in which the combination of the massage action and the shape of the turtle’s head and neck clearly conjure up the image of masturbation (see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DHpCjQ3_5tc). This situation is amplified by the high-pitched, human-like moans seemingly being made by the turtle as it enjoys the attention. The note to the recipient of the video in Figure 3, “Look at this cutie!” again invites the opening of the file with no warning. Even the strapline of the video only suggests being “creeped out”. As can be seen in the recipient’s response, the resulting affect revolves around the registers of panic and embarrassment.

The social and affective resonances of these examples are partly based on incongruities: that between appropriate computer use in the spaces of work and the consumption of porn for sexual titillation and masturbatory release; between the content suggested in the shared link and its actual content and user experience; between the publicness of the stunt and the assumed default privacy, or even secrecy, of porn and/or mobile media consumption; between the presumed normative heterosexuality or asexuality of public spaces such as offices and public transport and the loud, uncontrollable sexual resonances of the shared files.

At the same time, all the stunts, or “nimps” discussed above build on superiority – on laughing at the person subjected to them and, only slightly more indirectly, at gayness. Nimping in particular owed its power to the premise that being thus “caught” by one’s peers in watching gay male pornography would be a source of mortification and social amusement. Such trolling actions, conducted in the framework of straight male homosociability that manifest in most workplaces, tie gay porn and displays of sexuality more generally to the affective registers of grossness, shock, disgust and embarrassment. Normative hierarchies are thus re-articulated in the use of such a joke and in the requirement of recipients to respond with appropriate shame or mortification.

Larger mobile screens, combined with the indivisibility of work and leisure spaces they help to articulate, have expanded the range of sites that these dynamics associated with workplace humour and politics can be articulated. Considered in isolation from this broader fabric, a stunt, troll or nimp can come across as sheer fun and be about sustaining and building social relationships and a sense of belonging. They nevertheless equally create social exclusions and divides, relations of control and discrimination. The hyper-saturated communication contexts of mobile social media offer a wider range of such tools, not least with the default presence of larger screens. This all suggests that NSFW humour on the 4 inches of the mobile web is not to be taken lightly.

The blog post draws on the authors’ joint book-length inquiry Not Safe for Work: Sex, Humor, and Risk in Social Media, forthcoming from MIT Press.